As Nevada observes Wild Fire Awareness week, most state officials are keeping mum on what they expect this summer.

As Nevada observes Wild Fire Awareness week, most state officials are keeping mum on what they expect this summer.

“We are not predicting whether we will have a bad fire season or a light fire season,” said Living With fire director Sonya Sistare. “We know we will have wild fires and we need to educate people on how to cope.”

Sistare’s comments were echoed by Bureau of Land Management’s Public information officer Chris Hanefield.

“You can make some guesses regarding the amount of fuel and the rainfall in the winter and spring but the only way to tell how bad fire season is when its here. The conditions can change so rapidly that forecasts made in February or March may have no bearing on what June July or august will be like. We know there will be fires and we have to be prepared.”

The reason for the hesitancy to make a prediction could be because the chief cause of Nevada wild fires are thunder clouds that produce lightening but little if any rain as they sweep across the high desert in the summer.

A summer full of dry lightening clouds will have many more wild fires than one with fewer but whether summer clouds bear rain or lightening depends on that particular day when the cloud is overhead.

Another consideration is where the lightening hits. In a field of sage brush the strike could be relatively mild however a strike in over grown forest or worst yet in an area dominated by the invasive cheat grass a lightening strike could be the catalyst for an inferno that could claim hundreds of thousands of acres in less than a week.

Cheatgrass is the generic name for several types of annual brome grasses. The most common type, downy brome is most prevalent in Idaho, Nevada and Utah. For the past 150 years it has been waging a war of conquest and it is winning.

Dubbed cheatgrass by farmers it takes water and nutrients from cash crops such as wheat and alfalfa, the plant may have first arrived to North America in packing crates and spread by the railroad in the mid to late 1800’s.

Dubbed cheatgrass by farmers it takes water and nutrients from cash crops such as wheat and alfalfa, the plant may have first arrived to North America in packing crates and spread by the railroad in the mid to late 1800’s.

Originally from the Middle East and southeast Europe cheat grass’ spread with agriculture. Highly adaptive cheatgrass exploits germinates early and exploits soil disturbed by fire or agriculture. Not only does it exploit disturbed land its life cycle even encourages wildfire at a frequency and extent that native plants can’t compete.

And that is the secret of its success, from its lowly beginning as cheap packing material it now infests more than 100 million acres of land in the western United States making it the most abundant invasive species in the nation and is quickly replacing sage brush as the dominant plant in the Great Basin.

Cheatgrass is an amazingly prolific plant. A single stalk of cheatgrass can produce 1,000 seeds and an acre can generate more than 500 pounds of seed. In comparison, it normally takes just 10 to 20 pounds of grass seed per acre to establish a lawn in the typical American yard. Even at a mature height of just 2-4 inches cheatgrass can still flower and produce viable seed.

Cheatgrass usually germinates in fall or winter, continues to root and grow over winter and siphons away all available water and nutrients in early spring. But it is also extremely opportunistic. Given the right conditions it can germinate at any time during the year, quickly mature and germinate the next generation. While cheatgrass can be found in rangeland, ponderosa forests and even the desert, it’s most common in land that’s been disturbed or neglected, such as recently burned rangeland and wildlands, waste areas, abandoned fields, eroded areas, and overgrazed grasslands.

Cheatgrass usually germinates in fall or winter, continues to root and grow over winter and siphons away all available water and nutrients in early spring. But it is also extremely opportunistic. Given the right conditions it can germinate at any time during the year, quickly mature and germinate the next generation. While cheatgrass can be found in rangeland, ponderosa forests and even the desert, it’s most common in land that’s been disturbed or neglected, such as recently burned rangeland and wildlands, waste areas, abandoned fields, eroded areas, and overgrazed grasslands.

While its reproduction is prestigious the true secret to its success is the exploitation of fire.

Cheatgrass conquers with fire, it grows and germinates up to two months before most native grass and once it establishes a foothold, it dies leaving tender dry stalks ready to ignite.

And when it burns, it all burns. Wildfires in cheatgrass can travel over 30 miles an hour and the scorch earth left behind is perfect new territory for the next cheatgrass.

And sagebrush the dominant plant in the Great Basin acre by acre is slowly being replaced.

In the Great Basin, cheatgrass has shunted away the native sagebrush steppe and now dominates 25 million acres – roughly one-third of the region. That’s significant because sagebrush, in addition to being much less flammable than cheatgrass, also provides food and shelter for animals. A 2002 report from the U.S. Geological Survey reports that the loss of sagebrush ecosystems in the West negatively impacts many of the more than 350 species of plants and animals that rely on sagebrush for food or shelter. The Bureau of Land Management estimates that cheatgrass invades 4,000 acres each day.

While fire is a natural part of the sagebrush grassland ecosystem, fires in these types of areas usually occur at intervals of 60 to 100 years, and only burn a few hundred acres. In contrast, cheatgrass-infested areas burn at a frequency of every 3-5 years and consume hundreds of thousands of acres during one wildfire. The disparity is due to the fact that cheatgrass dries out early in the season, forms a continuous mat and is fine-textured, increasing its chances to ignite and spread.

While fire is a natural part of the sagebrush grassland ecosystem, fires in these types of areas usually occur at intervals of 60 to 100 years, and only burn a few hundred acres. In contrast, cheatgrass-infested areas burn at a frequency of every 3-5 years and consume hundreds of thousands of acres during one wildfire. The disparity is due to the fact that cheatgrass dries out early in the season, forms a continuous mat and is fine-textured, increasing its chances to ignite and spread.

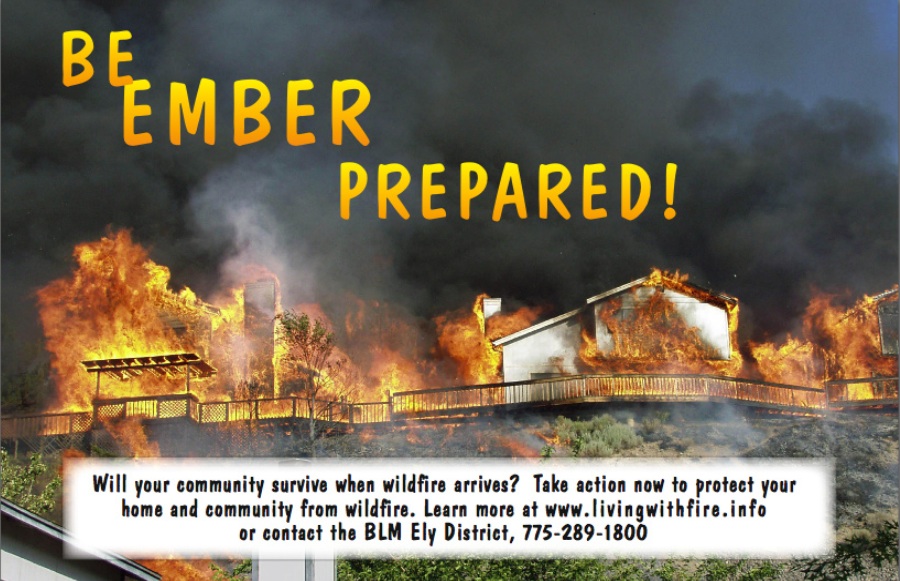

Because of the thick mat and flammability of cheatgrass, a cheatgrass-driven fire can be very dangerous to humans and dwellings standing in its way, shooting flames skyward 15 feet or higher. Some cheatgrass fires have traveled an estimated 20 to 40 mph, overrunning both firefighters and their equipment.

Fires that occur in areas with native vegetation burn in patches, leaving some areas of wildlife habitat remaining. But cheatgrass fires spread farther, carrying fire to otherwise isolated plant communities and completely devastating vast stretches of land.