“THIS MAY BE A HISTORIC MOMENT.”

The next star over has a planet that’s kinda like ours.

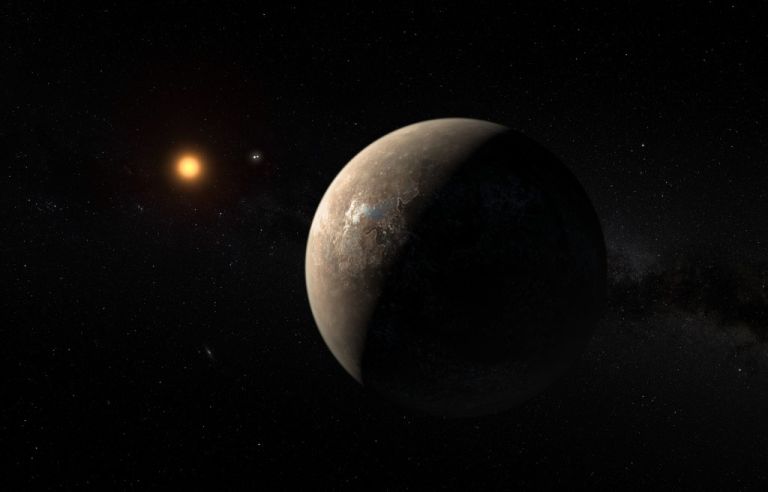

Astronomers just discovered the closest possible Earth-like planet outside our solar system. It orbits our closest neighboring star, Proxima Centauri. The planet is warm enough for liquid water, is almost certainly rocky and terrestrial, and could even have an atmosphere. At just 4.2 light years away, scientists are even wondering if this may be the closest home for life outside our solar system.

The newly discovered planet has been temporarily named Proxima B by its discoverers, an international team led by astronomer Guillem Anglada-Escudé at Queen Mary University in London. Proxima B is roughly 30 percent larger than Earth, and closely orbits a star far cooler and smaller than our own. Following a month of rumors and hints, Proxima B was unveiled today in a paper in the journal Nature.

“What’s amazing is how close it is,” says Jeff Coughlin, a SETI astronomer working with NASA’s Kepler planet-hunting mission, who was not involved in the discovery. “There’s nothing in physics that would keep us from sending a probe to Proxima B within the next few decades, even with just current day technology.”

The Hunt Begins

To appreciate what we know (and don’t know) about Proxima B, it helps to understand how the planet was discovered. Astronomers have not yet directly seen or snapped images of the planet. Rather, Proxima B was detected after roughly 16 years of analyzing telescopic recordings of the planet’s star, Proxima Centauri.

After combining all those recordings, scientists found the planet in a peculiar wobble of the star. They saw that Proxima Centauri wobbles toward and away from Earth in a cycle every 11 days plus a few hours . This movement can be detected in a slight shift in the color of the starlight, via the Doppler effect.

Overall, astronomers combined hundreds of observations. The effort recently ramped up after a tantalizing early whiff of Proxima B. Finally, the scientists determined that this wobbling is due to a delicate, tugging ballet between Proxima Centauri and a planet that orbits the star every 11.2 days. Although they could not see Proxima B, the astronomers could calculate the world’s size and distance from its star by crunching the numbers on Proxima Centauri’s wobble and estimated mass.

“THERE’S NOTHING IN PHYSICS THAT WOULD KEEP US FROM SENDING A PROBE TO PROXIMA B WITHIN THE NEXT FEW DECADES, EVEN WITH JUST CURRENT DAY TECHNOLOGY.”

This roundabout way of planet-hunting may sound uncertain, “but statistically there is no doubt about this signal,” says Anglada-Escudé. Taking this info Proxima B’s size and orbit, scientists have estimated that it is rocky like Earth and perfectly situated in its stars habitable zone, a place where liquid water should neither entirely boil nor freeze.

Red Dwarf

Proxima Centauri is not like our sun. It’s a cooler, smaller, and far more common type of star called a red dwarf. According to Ansgar Reiners, one of the astronomers behind today’s discovery who’s based at the University of Göttingen in Germany, this fact makes the case for life on Proxima B a more complex calculation.

For one thing, “Proxima Centauri is a relatively active star, so Proxima B receives rough 100 [times more] more high-energy radiation than Earth,” he says. Reiners is talking about stuff like gamma radiation that could be potentially fatal for microbes. But if Proxima B has a protective magnetic field and atmosphere like our own, then life could certainly still exist there—especially in oceans.

Proxima B is also pretty darn close to its star. Where Earth is 93 million miles from the sun on average, Proxmia B and its star are just 4 million miles apart—5 percent as far. Because red dwarfs are so much cooler than our Sun, the planet can be this close without getting charred to a crisp.

Yet this proximity could cause two problems. First, Proxima B is likely to be tidally locked, meaning the same face of the planet always faces the star. It’s like the way the same side of the moon always faces the Earth. (However, a thick enough atmosphere could keep the world twirling.) Second, depending on how and when Proxima B was formed, early blasts of stellar radiation could have blown away much or most of Proxima B’s hypothetical atmosphere.

That said, “none of this excludes the possibility of an atmosphere and water, it all depends on the history of the stellar system,” Reiners says.

Interstellar History

So just how big of a discovery is Proxima B? “This may be a historical moment,” says SETI’s Coughlin.

“I see this as the third phase of exoplanet discovery. Around 20 years ago, our first phase began as exoplanets first trickled in with one or two finds per year. The second phase was the Kepler era, where for the past 5 or 6 years we’ve been finding thousands and thousands of planets, and learning that even rocky, Earth-sized ones are incredibly common. Now we’re at the third phase. We’re beginning to look closer to home, finding nearby planets that humanity itself may one day be able to visit,” he says.

“I think today marks the start of our ability to map out the local universe around us, identifying the stars and planets in the sky that could be visited and utilized by our species, hundreds or thousands of years from now. I think humans will look back to this time as the very beginning of something,” says Coughlin.

As for the promise of life on Proxima B, Coughlin is cautious but hopeful. “The potential is there. I’d say we haven’t found any reason why life couldn’t be there yet,” he says.

Now that humans have detected Proxima B, Coughlin believes it’ll likely be a top priority for future space telescope missions. Astronomers the world over will seek ways to directly image it, uncovering the planet’s many unknown details such as whether it has an atmosphere.

Were it not for Proxima B’s close proximity to us, that would be an enormous challenge. The planet’s star, Proxima Centauri, is fairly dim by stellar standards, and the scientists believe there’s only a 1.5 percent chance that Proxima B actually passes in front of the star from our perspective here on Earth. That’s important, because if Proxima B eclipsed Proxima Centauri, it’d make a detection an easier task than picking it out of the darkness. That “transit” method is how Kepler found a lot of its exoplanets.

However, says Artie Hatzes, an astronomer at the Thuringian State Observatoryin Germany who was not involved in the research, “because Proxima Centauri is relatively close to us, such attempts have a reasonable chance of succeeding,” he writes in a essay in Nature accompanying the research paper. Beyond even ground-based or near-Earth telescopes, “in the distant future, an interstellar space probe might get a close-up look at the planet,” writes Hatzes.

For now, it’ll be fascinating to watch if Proxima B’s discovery jump-starts the search for other new planets around similarly close stars, ushering in Coughlin’s third phase. “We’re just starting to see the distant shores of the planets that may be out there,” says Coughlin.